Friends, I’ve got to tell you. I find it exhausting responding to White evangelical fundamentalist scholars and Black preachers who insist on keeping folks captive to hard and fast rules of scriptural exegesis for preaching, while not taking structural racism and social injustice seriously. I’m talking specifically about those who quibble about critical theory’s eclecticism and shut down conversations with “the Bible says” or “Show me where it says that in the Bible” theological arguments, as evangelical fundamentalists and radical biblicists so often do.

We must do better by the Holy Book. We can do better.

The Preacher’s Perfect Boogey-man

The origins of critical race theory are tied to legal studies, and curiously, like evangelical fundamentalism, critical theory was forged in reaction against liberalism. Black constitutional scholars such as Derrick Bell began developing critical race theory not as an engine for so-called “identity politics,” as often alleged, but to question the notion that the law is neutral and that every case has a single answer. For this reason, it should come as no surprise that critical theorists would draw on a range of sources and tools, both modern and postmodern, for interrogating claims of certainty, rejecting myths of objectivity and colorblindness, and calling into question unjust laws, policies, and structures that contribute to human oppression and inequality.

The Bible is inspired, but it is not self-interpreting. Homiletics professor Sally A. Brown rightly maintains that humans can’t not interpret because interpretative processing is the way all experience is navigated. Is it not possible for Christians to have a high view of scripture and still have a fulsome approach to investigating sources that feed interpretation? Or in the context of religious propaganda and raging debates about teaching CRT: Must one be a critical theory devotee to find value in philosophical insights that come from sources other than the Bible?

The Apostle Paul’s so-called Areopagus sermon, recounted in Acts 17, draws on Greek philosophy and stoicism to further his vision of the gospel’s agenda in the Greco-Roman world. “Both Seneca and Philo no doubt impacted Jesus’ teachings, if not directly at least indirectly, as they helped to shape the intellectual climate of which Jesus was a part,” notes Kelly Brown Douglas, dean of the Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary, and “to be sure they had a bearing on the thinking of the apostle Paul.” Moreover, one can even find parallels between Augustine’s use of Platonic ideas and the commitment of critical race theory to locate, analyze, and cut off ideological allegiances that mar personhood and perpetuate racial bigotry, human inequality, and economic injustice.

Critical theory is threatening only to those who are fighting to preserve white propriety.

What’s a Black Preacher to Do?

The first task is to question sources and unmask motive. I was recently messaged on Linkedin by an Anglo-American biblical scholar who posted a recap of John Albert Broadus’s “Brief Rules for Interpreting a Text” from his popular work “A Treatise on the Preparation and Delivery of Sermons,” first published in 1870. Here are Broadus’s rules for Bible handling preachers summed up: 1) interpret grammatically; 2) interpret logically; 3) interpret figuratively; 4) interpret allegorically; 5) interpret in accordance with, and not contrary to the teachings of Scripture.

Now in its fifth edition (2017), the publisher’s marketing pitch remains consistent with the first edition:

A Treatise on the Preparation and Delivery of Sermons – Fifth Edition is an unchanged, high-quality reprint of the original edition of 1870.

Many works of historical writers and scientists are available today as antiques only. Hansebooks newly publishes these books and contributes to the preservation of literature which has become rare and historical knowledge for the future.

Whose Future? Broadus’ Spiritual Progeny?

Who is John Broadus and why must Black preachers, really any preachers, take a moment of pause? Why is pausing not optional in an anti-CRT, anti-Black, “see no evil, hear no evil” American society? Here’s why. A quick bio: John Broadus was a Baptist pastor and former president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, a slaveholder and supporter of the Confederacy. Of his times, here is the man Charles Spurgeon called “the greatest of living preachers.” As long African American preachers tether their homiletical vision to Broadusian protocols as the gold standard for doing scriptural exegesis for preaching, debt peonage will be the African American preacher’s enduring pulpit legacy.

My response to the gentleman scholar who messaged me commending the book (without caveat) was:

Thank you, Prof. X. Now, I would say in response to your piece that preachers can get Broadus’s five rules achieved and miss the gospel for failing to take care to interpret texts interpersonally. New Testament scholar Brian Blount suggests that the “meaning potential” of a text such as Luke 4: 16-21, for example, should not be restricted to the classical canons of textual and ideational biblical interpretation alone where “meaning is understood to reside within the formal boundaries of a particular text’s language.” Rather, what should be explored and examined is the meaning potential of texts in relation to the interpreter’s interpersonal interactions with texts–namely, attending to the contextual elements in society wherein such texts are situated. Interpreters always come to texts with their questions, preunderstandings, and concerns.

Thus, since no interpretation of a text is prejudice-free, according to Blount, interpreters are themselves a part of the interpretative results. Therefore, to give one’s exclusive focus to textual and ideational concerns of Luke 4, in disregard of the interpersonal is to miss the Scripture’s offer of another revelatory channel. One major implication, then, is that an interpreter’s failure to consider the interpersonal dimension is to leave oppressed voices, like those to whom the text refers, on the margins and out of the interpretative process.

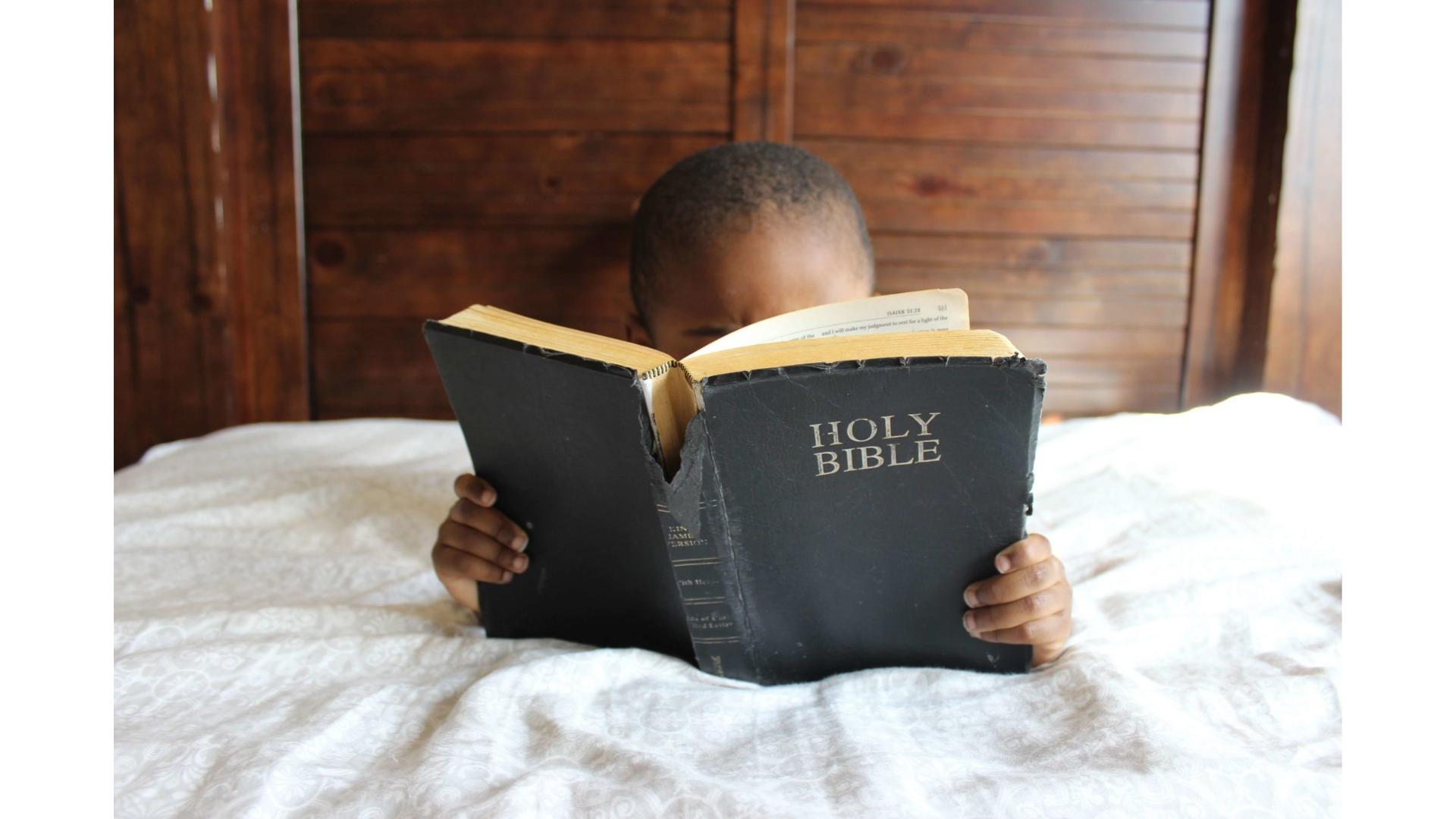

What does this mean for Black preachers who continue to say, “Show me where it says that in the Bible?” to ward off cultural critics. It means that if Black Christian preachers are not thinking about how the Broadusian homiletical loyalty system works, they can become merciless critics of movements such as Black Lives Matter and the Poor People’s Campaign while simultaneously being, at best, uncritical, passive allies of evangelicalism bound politically to pro-establishment or at worst, unwitting sympathizers for Confederate flag-weilding, “anti-establishment,” right-wing extremist. It means that the spoken Word from Black pulpits must demonstrate how a text functions and has meaning in the lived experiences of Black people and why the little lad pictured above with KJV in hand should trust the scriptures, appreciate its meaning potential for supporting his wellbeing in a society holding a high view of Scripture but low view of his Black body.

See: Brian Blount’s book Cultural Interpretation: Reorienting New Testament Criticism; Kenyatta Gilbert’s The Journey and Promise of African American Preaching, p.9-10;

“John Lewis and the Masks Black Preachers Wear on Public Stage” in The Conversation, August 12, 2020; and “Choosing Whiteness Over Witness: History Bends Toward Justice” in Sojourners, June 2021.